Wild Pantex – Partnering in Prairie Dog Research

Article by Jim Ray, Pantex Wildlife Biologist/Scientist

A lot of data has been gathered on black-tailed prairie dogs and associated species at Pantex. This has involved Pantex Natural Resources staff, Texas Tech University’s Natural Resources Management Department, U. S. Geological Survey’s Texas Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit at Texas Tech, and the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. As with the burrowing owl work (previously discussed), resources contributed through those external entities allowed inclusion of study sites from across the Southern High Plains of Texas for some of the objectives.

Upon examining aerial photographs, and following-up with ground-truthing, we found that the slopes above playa wetlands were very important to black-tailed prairie dogs in our region. Plain and simple, these slopes often escape plowing and thus hold remnant patches of prairie for prairie dogs and other wildlife species.

Estimates of black-tailed prairie dogs derived from procedures published by the Rocky Mountain National Arsenal were made in prairie dog colonies by Pantex staff, annually, during 2000-2003. Concurrently, Texas Tech conducted counts, while developing a model that considered date, time, temperature, and the number of prairie dogs observed. While, population estimates were very similar between the original method and the outcome of the new model, the model allows collection of the necessary data in far less time. This reduces the amount of time that busy biologists have to spend in the field conducting counts.

Through the use of grids of live traps we found that abundance of small mammals was similar between grasslands not occupied by prairie dogs, areas where prairie dogs were recently eradicated, and in active prairie dog colonies. However, in looking at individual species, two different graduate students found that the northern grasshopper mouse (Onychomys leucogaster) was more abundant in prairie dog colonies than at sites without prairie dogs. One of the graduate students found that the hispid pocket mouse (Chaetodipus hispidus) and harvest mouse (Reithrodontomys spp.) were more abundant on sites not occupied by prairie dogs.

Among birds, and certainly expected, western burrowing owls (Athene cunicuaria) were most abundant in study plots within active prairie dog colonies. However, the diversity of bird species was similar in areas with and without prairie dogs. One graduate student found that our summer resident bird species were most abundant in active prairie dog colonies, while migrant species were more abundant in plots without prairie dogs. Cassin’s sparrows (Aimophila cassinnii) and lark buntings (Calamospiza melanocorus) were most abundant on active colonies, while abundances of red-winged blackbirds (Agelaius phoenicerus), horned larks (Eremophila alpestris), chipping sparrows (Spizella passerina), and foraging barn swallows (Hirundo rustica) were higher on non-colonized sites.

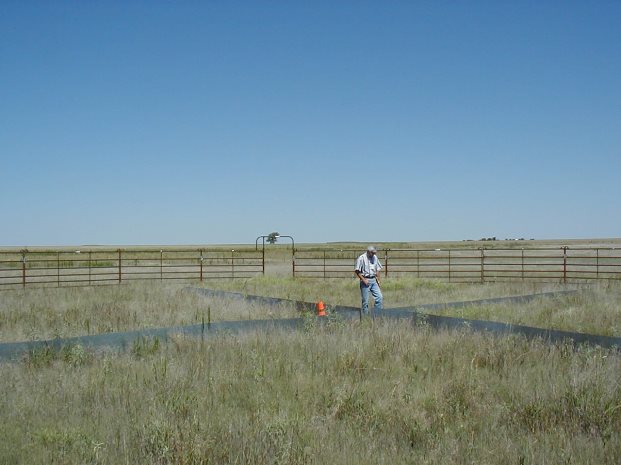

Our data indicate that ground-dwelling insects were more abundant in active prairie dog colonies than in shortgrass prairie not occupied by prairie dogs. Although the abundance of amphibians did not differ statistically between active colonies and unoccupied grassland, the number captured in active colonies was three times higher than what was found in the absence of prairie dogs.

The collaboration on prairie dogs with Tech has involved several students and resulted in two M.S. theses (McCaffrey 2001, Pruett 2004). To date, four peer-reviewed scientific publications (prairie vole, small mammals/invertebrates, prairie dogs, small mammals) have resulted from the work. Eight presentations on the work have been made at state, national, and international conferences, and even more at meetings characterized as less technical in nature.

Mapping of prairie dog colonies at Pantex is an annual management activity. In fact, mapping of the colonies dates back to at least 1996, making it perhaps the longest-running colony monitoring program for the species in the region.

Photo: This is a herp array, which are used to sample amphibians, reptiles and ground-dwelling insects. These creatures fall into buckets that are buried at the end of each "wing," including the center.